GLEN CINEMA PRIOR DEMOLITION c 1930

The cinema (opened in 1901), known as ‘The Glen’ and ‘The Royal Animated Pictures’ once formed part of the Good Templar Halls (now occupied by Burton’s shop). On the afternoon of 31 December 1929, during a children’s matinee, a freshly shown film put in its metal box in the spool room began to issue thick black smoke.

Soon the smoke filled the auditorium containing about one thousand children. Panic set in. Children ran downstairs so fast and in such numbers, that they piled up behind the escape door which led to Dyers Wynd. The door could not be opened, as it was designed to open inwards. The following day, Paisley was stunned by the news that seventy children had died in the crush in the worst cinema disaster in British history. The irony was, there was no actual fire.

Here is a short Documentary Podcast,

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/43820902″ params=”auto_play=false&show_artwork=true&color=ff7700″ width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Here are the picture’s of the Glen Memorial “all 4 sides” in Hawkhead Cemetery.

Find more information about the Glen Cinema by clicking the following link http://glencinema.paisley.org.uk/

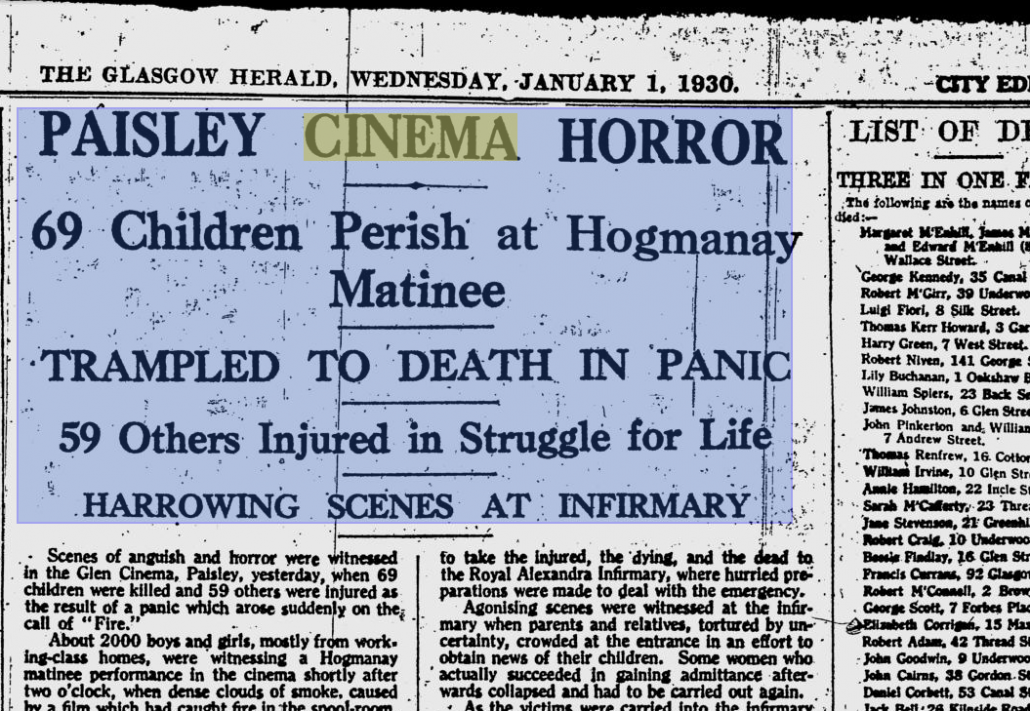

The Papers at the time of the disaster.

Click here for the full article.

Click here for the full article.

REMEMBERING PAISLEY’S ‘BLACK HOGMANAY’

“I remember I didn’t want to go that day,” said Emily Brown (95) – one of hundreds of children who attended Paisley’s Glen Cinema 90 years ago today for a packed matinee performance that ended in tragedy – forever remembered by survivors as Paisley’s ‘Black Hogmanay’.

The Glen Cinema tragedy took place on 31 December 1929 when a smoking film canister caused a panic during a packed children’s matinee where more than 600 children were present.

The main exit doors had a metal gate that had been pulled shut stopping it from opening leading to a crush where 71 children died, and more than 30 children were injured.

Robert Pope (97), had got up that morning and asked his mother for some jars to exchange for money so he could go to the pictures with seven of his friends.

Like so many children at the time, Robert and Emily were sent out the house to the cinema on Hogmanay to allow their parents to get the house cleaned and ready for the new year. They took their seats in the crowded theatre, sang their song and settled down to watch the new cowboy movie Dude Desperado.

During the picture a film cannister was placed on a heated surface and started to smoke up – leading to the panic and stampede which followed.

“I was there with my older sister Jean (10) and younger sister May (3) – we heard someone shout ‘fire’ and started to head for the exit. There was screaming and shouting, and people were pushing and trampling you and you were trampling on others trying to get out.”

“I remember some people jumped over the balcony or onto the stage to try to get out. I was separated from my sisters in the panic – I remember someone smashed a window and a fireman helped get me out.”

Emily’s aunt later found her wandering down Glasgow Road and took her home to her mother in Hunter Street. Her sisters Jean and May were already there and had managed to stay together during the chaos.

“I think my mother gave us all an extra cuddle that night,” said Emily.

“I don’t remember much about it,” said Robert. “I think my guardian angel watched out for me that day.

“When the panic started, I just remember something came over me and I stayed in my seat and didn’t move. I don’t remember much else until later when a fireman was clearing the hall, he asked me what I was doing. I told him I was waiting for the picture to come back on and he told me to head home to my mother and that the film wouldn’t be coming back on.

“My friends saw that I never came out and had told my mother I was still there, and she was getting ready to go up to the hospital to try and find me. As she opened the door, I was walking up the stairs and I remember the look of relief on her face. I think that saved her from the traumatic experience of seeing the children who had been killed and injured in the cinema at the hospital.”

Robert’s friend, William Spiers, who had sat beside him and fled during the panic did not survive the crush that day.

When news of the disaster spread through the town the entire community went to the Glen Cinema to try and help get the children out. Emily’s mother was one of those who pulled children from the cinema and loaded the injured onto trams for the hospital – not knowing if her children were safe or injured or worse. Emily’s mother was the only resident from Hunter Street who didn’t lose someone that day.

The funerals of all 71 children took place in early January of 1930. The town came to a standstill to pay their respects to those who died – everyone turned out including the hospital staff who treated victims and survivors and the Boys Brigade – who walked in the funeral procession. The children were laid to rest in Hawkhead Cemetery where a memorial still stands to remember all the victims of the Glen Cinema disaster.

News of the disaster was far-reaching with letters of condolence being sent to the town from people across the globe. The impacts were global as well – as the Cinematograph Act 1909 was then amended to ensure all cinemas had more exits, that doors opened outwards and were fitted with push bars. A limitation was also placed on the capacity of cinemas and a requirement for an appropriate number of adult attendants to be present to ensure the safety of children.

The Glen Cinema survivors and their families continue to commemorate the disaster every Hogmanay alongside members of the local community. They gather at 11am at the Cenotaph in Paisley town centre where they lay a wreath for those who lost their lives that day.

The Glen Cinema disaster of 1929 is considered one of Scotland’s worst human tragedies.