Canal Disaster

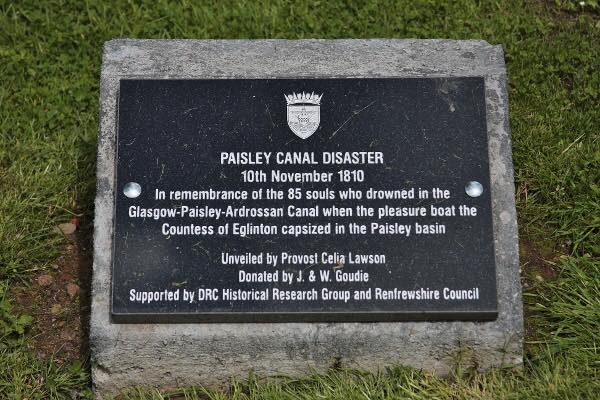

It is believed to have been Britain’s worst canal disaster, in which 85 people, most of them children, died when a pleasure boat capsized just days after the waterway opened.

Amy Szuster, assistant manager, outside the Canal Station Bar & Restaurant. Picture: John Devlin

But there is nothing to mark the horrific incident at the site of the canal basin in Paisley.

Now staff at an adjacent bar plan to put up a memorial to the tragedy nearly 210 years after one of the town’s darkest days.

It happened as crowds flocked to sail on the first section of the Glasgow-Paisley-Ardrossan canal, opened four days earlier in November 1810.

As passengers on the fully-loaded Countess of Eglinton boat from Johnstone crowded to one side to get ashore, others waiting to board rushed forward to get a space.

The boatman is reported to have moved the vessel away from the side to stop any more people jumping on, but it became top-heavy and capsized, with more than 100 being thrown into the water.

According to accounts, the canal was only about 6ft deep, but few of those in the water could swim and they were further encumbered by heavy winter clothing and the steep sides of the basin.

Among the children who died were several infants, one of them just six months old.

Workers at the Canal Station Bar & Restaurant, which occupies the former canal station on a rail line built over the waterway, want to put up a plaque to commemorate the disaster after a previous one went missing.

They have been spurred on by the unveiling on Friday of a Red Wheel plaque by the Transport Trust – the first in Scotland – to mark the building of the canal and the subsequent rail line.

Amy Szuster, the bar’s assistant manager, said: “There are plans to replace the plaque commemorating those lost in November 1810.

“It is early days, however plans will soon be developing.The canal disaster is a huge part of Paisley’s history and probably Britain’s worst canal disaster. It would only be right to commemorate those lives lost over 200 years ago.

It’s a really good idea to commemorate the event where it happened.”

William Cross, a writer and historian who runs a website about the disaster, said: “The death roll was a tragedy for many more folk as most victims were young people and some breadwinners.

“We must remember them, especially to inform the present generation of the very great sorrow there was in the town and district in past days.

“What was especially sad about the accident was it happened on Martinmas Fair, a holiday when people were out in numbers to enjoy themselves and have fun.

”Their working lives then were long hours for poor wages, and some of the more zealous of the passengers were no doubt a bit merry.”

John Yellowlees, who helped organise the Red Wheel unveiling, said it honoured the canal, which was constructed by Thomas Telford with the longest aqueduct span during the original canal-building age – Blackhall bridge.

The plaque also marks its conversion to a railway in 1885, which closed in 1983 before partially re-opening in 1990, with a new Paisley Canal station sited just east of the original.

The rest, including the stretch where the disaster happened, is now part of the national cycle network.

Yellowlees said: “The disaster is part of Paisley’s transport heritage so it would be good to see further commemoration of it.”

This article has been updated from our original with thanks to the Scotsman Newspaper.

—

The Paisley Canal Disaster

In 1791 the Earl Of Eglinton formed a company to build a canal from Glasgow to Ardrossan. Almost 20 years later, in 1810 the section between Paisley and Johnstone was completed and was duly opened on the 6th November that year with the launch of The Countess of Eglinton.

However, only 4 days later, on Saturday, 10th November 1810, disaster struck on Martinmas Fair Day holiday.

That fateful day being a holiday, a large number of families decided to take a trip on the newly opened canal. As the Countess of Eglinton barge returned from Johnstone to the Paisley canal basin with a full complement of passengers, large numbers attempted to board before the passengers from Johnstone had a chance to disembark. This led the boat to become top-heavy and it capsized, throwing the passengers into the water.

Eventually with the rise of the railway the canal was forced to close in 1881 and the canal was filled in and became the Canal Street Railway Line, running from Glasgow to Addrossan. However, in the early eighties this line was closed but re-opened later as the Glasgow to Canal Street line which stops just short of the original Canal Basin.

Much of the route of the canal can still be seen today although most of it is now a cycle path.

The section seen, right, runs along Canal Street bordering Castlehead Church.

The Paisley Canal Disaster was not the first death associated with the canal.

On 17th May 1810, whilst the canal was still under construction, and just 6 months before the canal was opened, Paisley poet Robert Tannahill drowned in a culvert between the canal and the Candren Burn.

In a fit of depression after a book of poems was turned down by publishers, Tannahill threw himself into a culvert on the Candren Burn. His body was pulled from this culvert which linked with the Canal. Tannahill was buried in the West Relief Churchyard – now Castlehead Church, and within yards of the Canal where he met his untimely death.

—

Accounts of the rescue from The Hidden Glasgow Forums

It happened as crowds flocked to sail on the first section of the Glasgow-Paisley-Ardrossan canal, opened four days earlier in November 1810.

It being Martinmas Fair, people were keen to try out a sail in the new canal boat.

As passengers on the fully-loaded Countess of Eglinton boat from Johnstone crowded to one side to get ashore, others waiting to board rushed forward to get a space.

The boatman is reported to have moved the vessel away from the side to stop any more people jumping on, but it became top-heavy and capsized, with more than 100 being thrown into the water. Few of those in the water could swim and they were further encumbered by heavy winter clothing and the steep sides of the basin.

The following is an account from the time of how other passengers and local bystanders helped to rescue some of the victims from the canal water.

While some of the crowd ran off to procure ropes, creepers, boards, others rushed into the boat, in hopes of saving some by dragging them up the side of the vessel; but in their eagerness to accomplish this almost proved fatal to themselves, for by crowding all to one side of the boat, they had nearly occasioned a repetition of the fatal accident, and but for the actions of Mr. Barclay, from the opposite side, and others it is probable that a second disaster, similar to the first, would have been added to the horrors of this calamitous scene.

By the exertions of Mr. Jameson and others on the wharf, the boat was made fast with ropes, and great numbers of bodies, many of whom exhibited signs of life, or were afterwards recovered were drawn up by the cabin top or windows. In the meantime, the two boatmen and several other (The water in the basin is about eight feet deep) persons who were thrown into the water, had gained the opposite bank where, with more of the spectators joined Mr Barclay in helping to save the lives of those who floated within their reach.

Lawrence Hilt, an old man, and one or two other persons, who could swim, stripped and went into the water, where they succeeded in rescuing many from the death that threatened them.

The people in the boat too, and on both tides of the basin, quickly helped in picking up bodies and conveying them ashore, while others carried them off to the neighbouring houses,

To the credit of the inhabitants residing at that part of the town it must be mentioned, that every house was open to receive them, and all the useful materials their owners possessed, were at the service of the medical gentlemen or others employed in the process of resuscitation.

A vast crowd was collected from all parts of the town—every heart seemed interested—every hand was ready to lend assistance. The result was, that the lives of about one hundred and twenty persons were saved—a few having gained the bank by their own exertions—a number being brought out alive by the activity of the people.

Eighty-five persons in all were drowned, many of whom, there is no doubt, lost their lives in consequence of receiving contusions , or of being pressed down in the water by those who fell above them, or entangled with, those that floated around them

In particular Robert Barclay, Esq: was most eminently conspicuous, and entitles him to the gratitude of every lover of humanity. When the boat arrived from Johnstone, he was in front of his own house, above the basin and quickly perceiving the danger to be apprehended from the number and turbulence of the crowd then collected in waiting for the vessel, he ran down to the bank of the canal, using every endeavour, by his cries and gestures, to warn them of the risk they incurred by rushing tumultuously into the boat. When the fatal accident happened he was most useful, by his presence of mind, his personal exertions, and his influence with others, in extricating numbers alive from the water.

While so engaged, a child, apparently dead, was committed to his care, which he immediately carried to Peter Wright’s house, and never quitted till he had succeeded in restoring animation.

His own house was thrown open for the reception of bodies, and whatever it contained that could be useful, was cheerfully furnished. He attended in person, to give every assistance in his power, while all the members of his family joined in giving any other help needed.They enjoyed the satisfaction of seeing their services prove signally useful, and the blessings of many that wore ready to perish have come upon them.

Lawrence Hill, an old man of seventy years of age, deserves next to he

particularly mentioned. By his intrepid exertions—exertions made at the

risk of his life, and beyond his strength, and from which his advanced years

might have been deemed an excuse—several lives were saved.

He stripped and went into the basin, where he continued swimming about, and conveying bodies within reach of the people at the cabin windows, till, checked with cold, he had to be himself assisted in, and afterwards conveyed to a bed in

a neighbouring house.

The exertions of Alexander Whitehill of Elderslie, should next be noticed,

who, after swimming ashore to save his own life, stripped and brought out six others, till, checked by the cold, he was obliged to be assisted himself.”

Local medical people did all they could to revive passengers including many children who appeared drowned but by using recommended methods of resuscitations of the time managed to save many lives.

Following the disaster one Dr. Kerr, spoke at the Philosophical Institution of the success of the methods of resuscitation used. This was great discussed by all present.